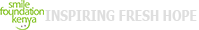

A true story and study of Nairobi’s street children and the people working to uplift them. Some names have been changed to protect identities.

Capitalis

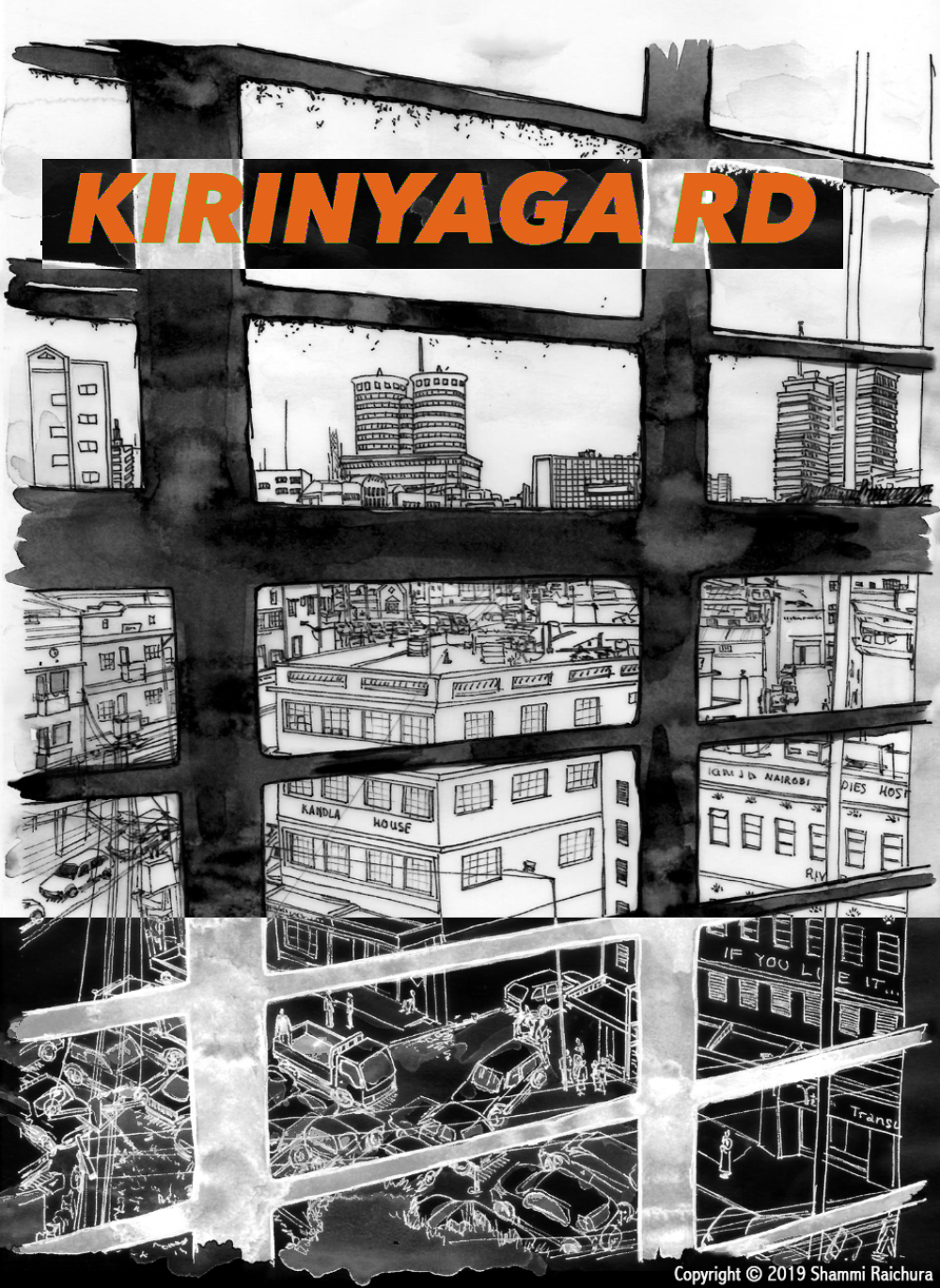

[Eron Hotel, 5th floor, Kirinyaga Road, Nairobi, Kenya]

[16/04/18 23:43]

I walk to the far side of the hallway and look out north over the open stairway towards Nairobi River. By night, the only lighting in the yard is provided by the intermittent flashes of welding sparks and the dim hue of kerosene lamps and solar lights. From this vantage point, perceptions of my surroundings are better guided by sounds – the yard is alive with a baseline murmur of clattering and distant conversations. The smell is of dust and unpleasant burning. During the day, the stories behind the smells and sounds reveal themselves; old discoloured plastic goods, smoke plumes, rusty iron corrugated roofs and people… lots of people.

Like all cities, Nairobi has many sides to it. I’m here to learn another one of its stories, surfaced right from the within the city’s underbelly.

[17/04/18 16:43]

I leave my room and walk towards the lift, glancing out through the tired window on the south wall which overlooks Kirinyaga Road. I’m staying in the CBD; the ever hustling epicenter of the city.

The short walk to my destination on Moi Avenue is one that needs a degree of mental preparation. If you aren’t about your wits, there is a high chance you may be overwhelmed by the busy streets and find yourself having tripped over into an open drain or caught in the line of traffic. Maybe both concurrently.

I pass through the Koja bus stage along my route. It’s confusing with no orderly movement of people, vehicles, trolleys or cargo. I was advised by a friend not to attempt crossing it after dark as “You will probably get ran over, it happens daily even to us Kenyans”. I like to think of myself having a degree of street smarts about me, and travel prepared with my wits and a bright torch for these situations – which usually occur multiple times per day if you are out exploring and not lounging by a hotel pool in Westlands.

But even then, staying alert to your surroundings can only minimise any unwanted incidents, and never completely remove you from their advances. Only the day before, I was approached by a plain clothed police officer who had been following me because he thought I was a terrorist – apparently because I was ‘walking quickly’. When retelling the story to my Kenyan friends, they said I must have handled the conversation with the officer well, given I didn’t end up in a jail cell or my hand wasn’t forced into bribing him. I think I was just lucky.

Once you reach Moi Avenue, things become a little more orderly. I cross over to Bihi towers, where the security guards no longer search me as I enter because I’m a frequent visitor (not the most robust qualification criteria for building security, but this somewhat commonplace in Kenya).

I enter the lift and zip up to the 13th floor, flicking through the pictures I had just taken on my phone. During my walk, I had passed by eight street children. Photographing people in despair is not a hobby of mine, but it was something I had done during my journey – in anticipation of the interview I was about to undertake and with the view to writing this.

I was meeting Bradley Kivairu. He runs a charity called Smile Foundation Kenya and I wanted to hear his story. That’s the main reason why I was on this trip – to gather people’s stories, learn and help where I can by giving them a voice.

What you are about to read is a story about real lives.

True trials and tribulations.

Real death, real despair.

But importantly, real resurrections.

This is the true story of Bradley Kivairu and the Riverside Children of Nairobi.

[Bihi Towers, Moi Ave, Nairobi, Kenya]

[16/04/18 17:02]

Bradley

“Everything about me is Nairobi!” He tells me as we place an order for mango juice. ‘I was a smiley child but didn’t speak much. I wanted to help people and developed an interest in doing so from a young age”.

Bradley was telling me what it was like growing up in Nairobi and where his calling for creating solutions to help the less fortunate all began.

“I went to an all boys boarding school which had an array of children from different backgrounds. I ended up turning into an unofficial representative of the pupils from poor families – by approaching the rich pupils to ask them to donate toiletries, stationary and clothing to be given to those less well off. This would stop the poorer children from stealing and getting themselves into trouble”.

“Eventually the school gave me permission to go from class to class, explaining the initiative and spreading the word. The well off pupils started going away on breaks and bringing back items to be donated. The poorer pupils didn’t want to be looked down upon in pity, so the system was kept anonymous on both sides. I ended up helping 100 kids”.

Fast forward to his late teens and Bradley is working as a sound engineer. He would often think about his passion for helping people that he enacted upon in high school – and how he may be able to get back to doing so despite his families advice to keep a ‘proper job’.

Every street is the start of a story

It’s September 2013 and Bradley is walking through town when a young street boy named Masharia approached him and asked “Brother, can you help me?”.

“How can I help you?” he replied

Bradley approached the conversation with caution. He had heard of and seen too many incidents involving street children which ended badly. Notably the stories of street children at Globe Roundabout – where in the 90s they were known to carry bags of their faeces which they would threaten to fling at you if you did not comply with their demands.

Masharia was very clearly high on some form of drugs and was asking for food. Bradley wanted to know more, so he asked him “Brathé, [Sheng for brother], aside from begging what else do you do? You’re a young guy, do you go to school?”.

No response. Young Masharia was too out of it to partake in a conversation.

After some more unsuccessful probing, Bradley gave him the little money he had in his pocket. Masharia was grateful.

The next, day Bradley returned to the same spot and walked back and forth trying to find Masharia, but he was not there. Somebody different was begging in the same spot, but Bradley was reluctant to approach him so stuck around until the boy noticed Bradley and walked over. His name was Samuel, and he proceeded to ask Bradley to buy him some food. Bradley attempted a similar line of questioning with Samuel as he had with Masharia; “Do you have family? Are you in school? Do you have parents?”.

Bradley gained what little information he could and gave Samuel 100 shillings.

At this point, Bradley was intrigued as to the reason for the plight of street children, so he began conducting some research. The most recent credible source of information he could find was from 2007, but it seemed incomplete and somewhat unreliable. There wasn’t much available online about the street children of Nairobi so he thought to himself; what better way to learn than directly from the children?

He had heard about a community in Kware, a low income ward of Nairobi containing a slum – well known as being a dangerous part of town. Kware had a river running through it that was (and still is) polluted to the point that it was black in colour. Word was that after 6pm, Kware becomes impassable… unless you wanted to get robbed that is.

Post a comment