Every base has a leader, known as a ‘master’ who is typically the eldest. For groups with older members, most masters are aged between 18 and 25. If there is no standout elder, then the master is usually the one who is known to be the most fearless, reckless and respected individual.

The master typically gets younger members of the group to undertake high risk tasks such as pedalling drugs and weapons, not caring if they end up being caught. Street children usually spend their days undertaking tasks around town before returning to the base at night. For some, this can mean leaving early in the morning with a sack, looking to collect scrap metal or plastic. Plastic can be sold on at a rate of 10 shillings per kilogram (less than 10 pence). Their haul varies every day, and if they are lucky they might bring in 10kg which usually leads them to taking a few days off. Either way, the master gets a cut.

Some members play for higher reward by engaging in theft of scrap metals from garages or housing estates. Metal can trade for 17-20 shillings per kilogram, so one good lump of metal can reap a decent return.

The bases themselves have no physical structure, and are open areas usually with suspended nylon canvases as makeshift weather protection in the absence of permanent shelter. Bases are normally extremely dirty, as the members bring food from bins that has been thrown away to eat what they can – and the remainder is disregarded at the base.

Life on the street

Street life usually begins as a result of the limited prospects faced by families living in inner-city slums. Slum dwellings are typically 10ft x 10ft structures with around 7 people living in one space. Families often end up in slums because they leave rural areas of the country and come to cities chasing opportunity. In 2014 it was estimated at 56% of Kenya’s urban populations lived in slums. This statistic is reflected in Nairobi where 2.5 million people live across slums such as Kware, or the more well known Kibera Slum – the largest in Africa.

Parents of slum residing families are usually occupied trying to make ends meet, whilst often also facing difficulties with alcohol and drugs. Most families have a number of children and many of them don’t receive the attention and care they need to strive in such an unstable and unsafe environment.

Some children get moved on the other guardians such as aunties, uncles or grandparents from whom they often escape. Others are orphaned after the premature death of parents and default to life on the street. A common circumstance would be a child from a single parent household (usually a mother) who is struggling to raise her children. Such a child succumbs to the allure of earning money in the street after hearing about it from peers. This is the start of their life on the streets.

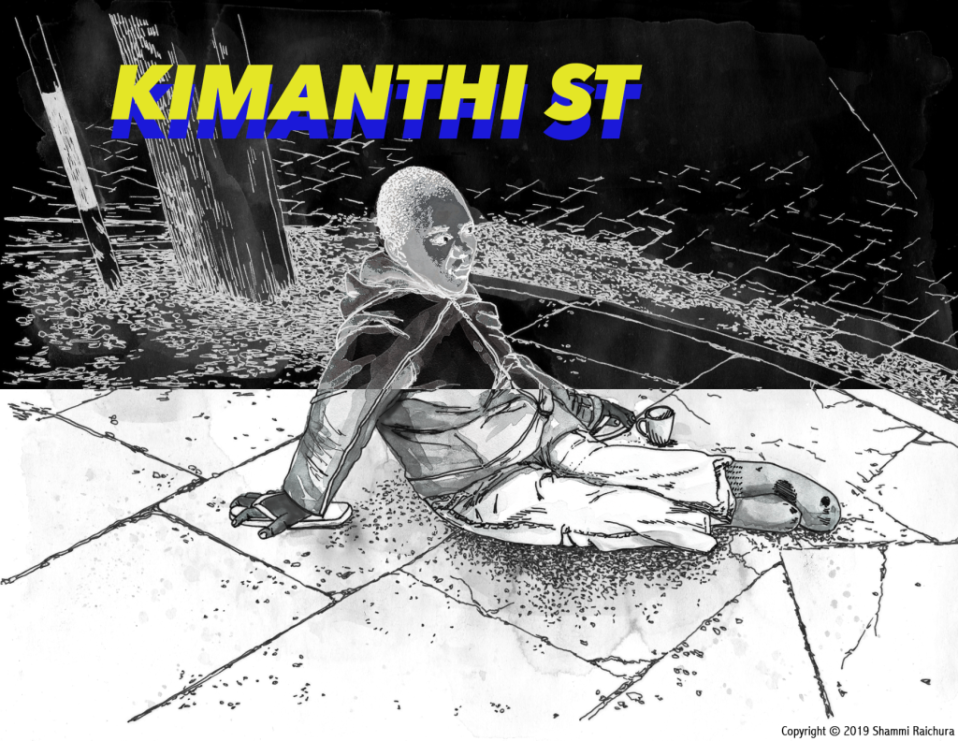

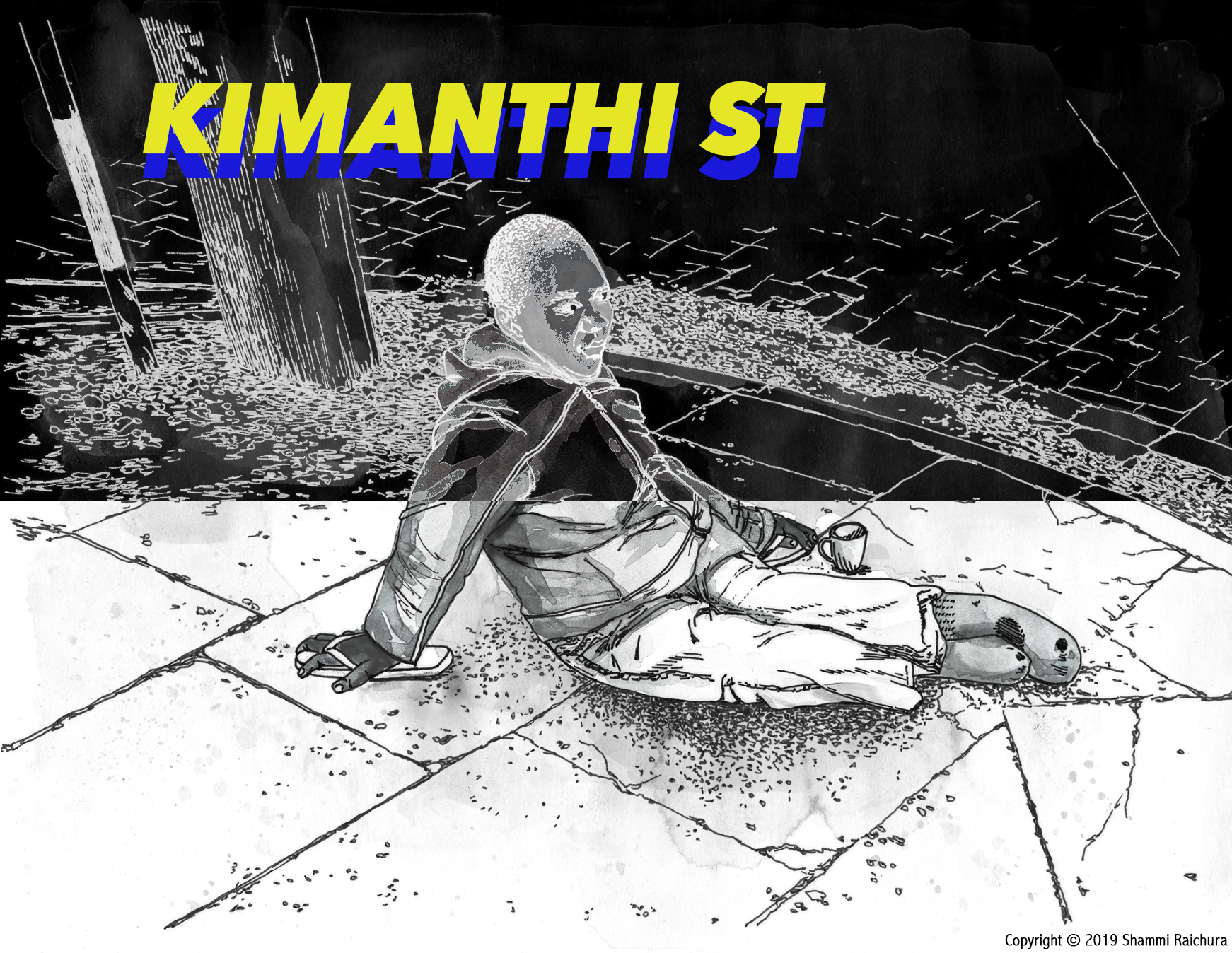

Once children or young men get involved with a base, many lose connection with their parents. Outside of hustling hand to mouth, street children also engage in highly addictive substance abuse. This typically involves the use of industrial strength cobblers glue – sniffed to give them a prolonged numb feeling. More recently, the use of turpentine is on the rise as it is ever more abundant, cheaper and easier to hide.

When using glue, children can be seen with bottles or bottle caps containing residue. Police will sometimes take any child sniffing glue to a jail cell (a band-aid approach to solving the problem). Turpentine use is more concealed since the liquid is clear and can be sniffed from a rag that’s been dipped inside it. The effects of turpentine are more short lived but more intense than glue – delivering an instant feeling of spinning in the head.

Older group members take advantage of these substances as a means to exert control and coerce younger members of the group. Children can’t access turpentine in shops so older members of the group buy it for them in return for favours. The most favoured street children in a group are often given special treatment and privileges such as protection or more drugs and alcohol.

How does it end?

For boys, more than 70% don’t make it past the age of 21. Common causes of death include falling to the wrath of street violence or at the hands of police. The most concerning? That many street children are caught stealing by community members who have been known to then deliver mob justice, resulting in them being beaten to death. If they don’t die in the process, then they are left to die in the street.

Females

Young girls are very rarely seen in the streets. Usually for one of two reasons.

Most of the time, girls in the streets are there to gain favours from the passing public in the form of money food and clothing. From a young age they learn to taking advantages of this – female adult beggars in Nairobi are often from the slums, bringing their kids with them to gain sympathy from a well wisher. Many older females default to undertake this as their primary source of income.

Fortunately there exist many support channels and organisations for young girls on the street, meaning less are falling through the net.

For those younger females in the street who do not have access to services, their fate is somewhat bleak. In most cases, these individuals do not have information on how to gain help or do not have the means to accessing it. Some of them will end up in a base made up solely of boys and young men.

In a base, their acceptance is usually attained by them being gang raped by the males in the group. Usually, any such female in these circumstances will end up becoming ‘the masters girl’. These girls are typically aged 15-17, but on odd occasion they can be as young as 10 years old. They are given housing and food and seen as ‘property of the master’. These girls are usually only then used for sexual favours by the master, and in the event that she is taken advantage of by another male in the group, it may end with the master taking her life.

In the absence of support, most of girls end up having several children with different men. These children born into the streets, and usually remain in the streets.

State intervention

The state runs accommodation locations and rehabilitation centres for street children. From what Bradley tells me, these centres reap mixed results as it would seem they are not always ran effectively. Often, many of the children and young people who should benefit from the services at these centres end up running away. More effort needs to be made to build relationships and connections with the children and young people at these centres. Delivering care and rehabilitation through compassion and by creating personal bonds will lead to more of them wanting to stay – so they do not have to look to the street to fill this void. Currently, many centres are delivering a service provision which is transactional and routine in its nature – with not all staff having the passion required to go the extra mile, often due to pressure from limited resourcing capacity.

Outside of their own direct service provision, local governments are reluctant to fund third party organisations because of bad experiences. Numerous times they have been stung by organisations taking money and then disappearing.

Largely, many of the government’s efforts are aimed at addressing the effects of street children and not the cause. Work is required to address the root cause of how family units fall apart in slums – and a level deeper than this, to consider the underlying drivers which lead families to leave a more comfortable life in rural areas to make their way to a city. Managing and understanding the movement of people should be given equal consideration to those efforts addressing families who are already in slums without work, looking after children who are outside of the education system.

The narrative

There is a clear need to recognise the damaged culture and harmful narrative which can slow down efforts being made to alleviate the plight of street children. During the same week I met Bradley, I came across two news articles linked below, they show how dehumanising some of the the language used to describe street children is. Street children are spoken of as though they are vermin, which need to be ‘flushed out’ – this sentiment finds its ways into local communities and every crevice of society, making it less likely that street children are treated with compassion.

‘Sonko flushes out street children from Nairobi CBD – PHOTOS’

‘Street children flushed out of Nairobi CBD in impromptu operation’